Then I am the healthiest person on the planet. When I went to bed last night at 11pm I remained awake since 7am from 2 days before. 40 no sleep. All working.

I have been worried about my sleep pattern and constant lack of it for a while.

What about you?

Sleep: are you getting too much of it?

Sleep is a rare commodity, a luxury of which most of us feel deprived. We’re kept awake by the stress of our work, our children, the blue screen light of our gadgets and even by the anxiety that we can’t get enough sleep. A lot of us fail to achieve the gold standard eight hours a night touted as essential for health, creativity and a quick-thinking mind. We visit sleep clinics in droves, download sleep apps and buy supplements, £100 pillows, anything that promises to achieve a decent night’s shuteye. And most of us still think we fall short.

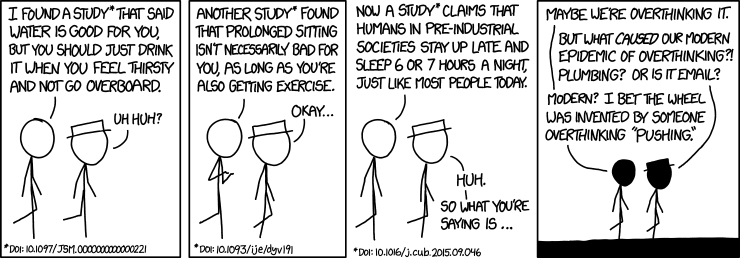

But are we chasing a futile dream? Last week, the idea that we are suffering mass sleep deprivation was thrown into question by experts reporting in the journal Current Biology. Jerome Siegel, professor of psychiatry at the University of California, and his team believe that we are obsessing unnecessarily about how much sleep we get. In fact, their research shows that the nocturnal habits of those living in modern, industrialised societies are not much different from hunter-gatherer and hunter-horticultarist societies in Africa and Bolivia, who have lifestyles similar to our paleolithic ancestors.

Our rest is reduced by the lightbulb, the internet and social media, theirs by fussing with furs and campfires. The outcome, though, was similar. Tribes stayed up well past sundown and a typical night’s rest amounted to 6 hours and 25 minutes. What’s more, their health was seemingly unaffected.They had lower rates of obesity, better fitness levels and healthier hearts than people in industrialised societies.

“People are always saying we sleep a lot less than we used to, and that is started with electric light,” said Siegal. “But how can that be the based on hard data? We’ve only been able to measure sleep properly for the past 50 years.”

Their study is just the latest to suggest that our sleep fixation has spiralled out of control. It follows another report last month in the journal Sleep Medicine Reviews that revealed very few of us are, in fact, yawning our way through life. Analysing data from 168 studies on more than 6,000 adults between 1960 and 2013, the team of sleep researchers from several American universities concluded that there is no widespread sleep deficit. Far from it.

In fact, most people are not only spending enough time in repose but have been doing so for the past 50 years. Ironically, suggests Professor Shawn Youngstedt, of Arizona State University, one of the paper’s authors, the more that we think about missed sleep, the more we are likely to experience the kind of anxiety that prevents it. It has become a self-perpetuating problem, he says, with insomnia being “triggered or exacerbated by excessive worrying about sleep”.

This, I can relate to. For years I’ve luxuriated in seven and a half hours a night of restful slumber. Yet in recent weeks one thing and another (the dog barking, child waking, a meal eaten too late) has caused uncharacteristically interrupted nights. By morning, I have felt so heavily in sleep debt that I fixate on catching up. It’s easy to see how it could snowball into an unhealthy obsession.

Dr Irshaad Ebrahim, the medical director of the London Sleep Centre, says most of the clients who traipse wearily to his clinic are not as unrested as they think. “In general, most people are getting enough good-quality sleep, and sleep disorders are definitely less common than people are led to believe,” Ebrahim says. “There are pockets of the population who are more likely to experience chronic lack of sleep, such as people who live in big cities or who use electronic devices late at night.”

Mostly, he says, people present with what they think are symptoms of a sleep problem, but are in fact perfectly normal variations. “Over the past decade people have become so much more aware of sleep loss,” he says. “They think more about it and have developed this unhealthy preoccupation with it.”

What, then, should be our aim? Professor Kevin Morgan, of the clinical sleep research unit at Loughborough University, says the notion that we require an eight-hour block of sleep a night is little more than an urban myth and a “colossal nonsense”. Nobody knows where it came from, he says, “yet somehow it got stuck like a nasty virus in the public mindset”.

He suspects there has been commercial encouragement of the eight-hour myth to fuel the growing industry for sleep-enhancing products and treatments on sale. Yet science has confirmed it is impossible to quantify the ideal sleep duration. Needs change as we age — we need less rest at 50 than we do at 30, even less when we get to 70 — and with fluctuations in activity levels along with other factors such as illness. There is a huge variety in sleep requirement, even between siblings. “It’s an extremely dangerous message to apply standard metrics to sleep,” Morgan says. “Most adults don’t need anywhere near the eight hours held up as the norm, and it sets them up for failure if they try to achieve it.”

Dozens of surveys show that roughly 90 per cent of the UK population reports getting six to nine hours’ sleep a night although, probe the data more closely and the majority are at the lower end of that spectrum. Some studies are prone to subjective bias; because people think that they need eight hours, they are more inclined to report getting it. In reality, a greater percentage function on considerably less, somewhere around the six-and-a-half-hour mark.

Typically, people with insomnia are poor judges of how much slumber they get, misjudging how long it takes them to fall asleep and how often they wake up. Many think they sleep for fewer hours than they actually do. In one study, 42 per cent of people with insomnia underestimated their sleep total by an hour and other research has shown that about half of those who believe that they have sleep problems amass at least six hours a night, which, says Professor Morgan, is perfectly adequate.

“I can’t remember when I last got eight hours of sleep,” Morgan says. “I don’t need it. Sleep should be thought of not as a random number, but as an experience. You need just enough to feel refreshed the next day.” That can be as little as five hours for some people, as much as nine for others. “It’s actually OK to feel tired occasionally,” Ebrahim says. “Only if you are chronically exhausted do you need to seek help.”

Way too little sleep has been linked to increased risk of high blood pressure, diabetes and obesity. However, it’s not always helpful to get more sleep, even when you think you crave it. Indeed, it can backfire. “There is a constant in the epidemiological literature that regularly sleeping for more than eight hours is by far the strongest predictor of mortality,” Morgan says. “The risks to health are at least as significant as for those who sleep for less than six hours.”

This year academics at Cambridge University who observed the nocturnal habits of 10,000 people confirmed that sleeping for longer than eight hours doubled the risk of stroke in people aged 42 to 81 years. Those who slept for more than eight hours a day were found to be at 46 per cent greater risk of suffering a stroke than average. “It’s fair to say that levels of sleep literacy are extremely low, that people have little understanding of what they need and why,” Morgan says. “Too many think that more time asleep is better, when it much more risky to health to get consistently too much sleep than too little.”

http://www.thetimes.co.uk/tto/health/article4590272.ece