Who will win the COVID-19 Vaccine stakes ?

Rumor has it that the Greeny who fabricates a "link" between COVID-19 and Global Warming will be awarded the Greeny Nobel Prize.

Coronavirus vaccine: when will it be ready?

Laura Spinney Mon 30 Mar 2020 00.57 AEDTLast modified on Mon 30 Mar 2020 00.58 AEDT

Human trials will begin imminently – but even if they go well and a cure is found, there are many barriers before global immunisation is feasible

When will a coronavirus vaccine be ready? Illustration by James Melaugh. Illustration: James Melaugh/The Observer

Even at their most effective – and draconian – containment strategies have only slowed the spread of the respiratory disease Covid-19. With the World Health Organization finally declaring a pandemic, all eyes have turned to the prospect of a vaccine, because only a vaccine can prevent people from getting sick.

About 35 companies and academic institutions are racing to create such a vaccine, at least four of which already have candidates they have been testing in animals. The first of these – produced by Boston-based biotech firm Moderna – will enter human trials imminently.

This unprecedented speed is thanks in large part to early Chinese efforts to sequence the genetic material of Sars-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19. China shared that sequence in early January, allowing research groups around the world to grow the live virus and study how it invades human cells and makes people sick.

But there is another reason for the head start. Though nobody could have predicted that the next infectious disease to threaten the globe would be caused by a coronavirus – flu is generally considered to pose the greatest pandemic risk – vaccinologists had hedged their bets by working on “prototype” pathogens. “The speed with which we have [produced these candidates] builds very much on the investment in understanding how to develop vaccines for other coronaviruses,” says Richard Hatchett, CEO of the Oslo-based nonprofit the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (Cepi), which is leading efforts to finance and coordinate Covid-19 vaccine development.

Coronaviruses have caused two other recent epidemics – severe acute respiratory syndrome (Sars) in China in 2002-04, and Middle East respiratory syndrome (Mers), which started in Saudi Arabia in 2012. In both cases, work began on vaccines that were later shelved when the outbreaks were contained. One company, Maryland-based Novavax, has now repurposed those vaccines for Sars-CoV-2, and says it has several candidates ready to enter human trials this spring. Moderna, meanwhile, built on earlier work on the Mers virus conducted at the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in Bethesda, Maryland.

Sars-CoV-2 shares between 80% and 90% of its genetic material with the virus that caused Sars – hence its name. Both consist of a strip of ribonucleic acid (RNA) inside a spherical protein capsule that is covered in spikes. The spikes lock on to receptors on the surface of cells lining the human lung – the same type of receptor in both cases – allowing the virus to break into the cell. Once inside, it hijacks the cell’s reproductive machinery to produce more copies of itself, before breaking out of the cell again and killing it in the process.

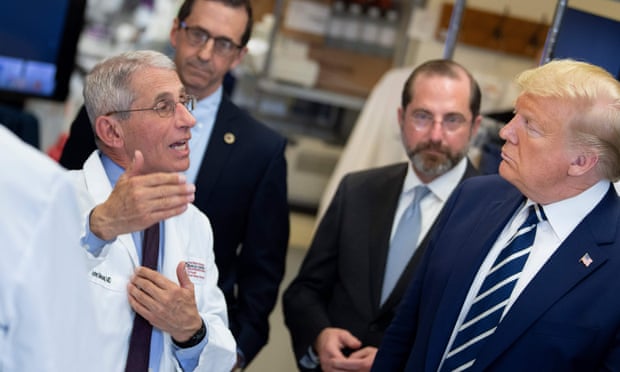

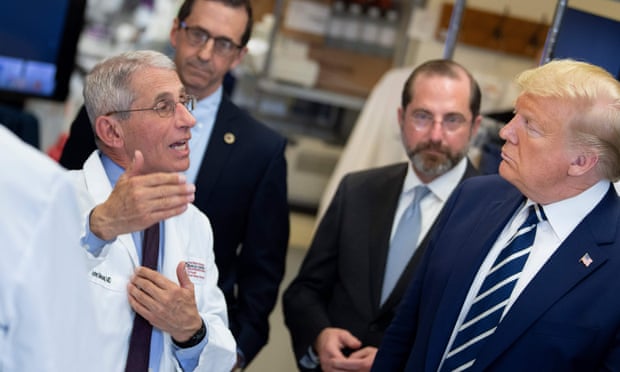

Donald Trump at the National Institutes of Health’s Vaccine Research Center in Maryland, 3 March. Photograph: Brendan Smialowski/AFP via Getty Images

All vaccines work according to the same basic principle. They present part or all of the pathogen to the human immune system, usually in the form of an injection and at a low dose, to prompt the system to produce antibodies to the pathogen. Antibodies are a kind of immune memory which, having been elicited once, can be quickly mobilised again if the person is exposed to the virus in its natural form.

Traditionally, immunisation has been achieved using live, weakened forms of the virus, or part or whole of the virus once it has been inactivated by heat or chemicals. These methods have drawbacks. The live form can continue to evolve in the host, for example, potentially recapturing some of its virulence and making the recipient sick, while higher or repeat doses of the inactivated virus are required to achieve the necessary degree of protection.

Some of the Covid-19 vaccine projects are using these tried-and-tested approaches, but others are using newer technology. One more recent strategy – the one that Novavax is using, for example – constructs a “recombinant” vaccine. This involves extracting the genetic code for the protein spike on the surface of Sars-CoV-2, which is the part of the virus most likely to provoke an immune reaction in humans, and pasting it into the genome of a bacterium or yeast – forcing these microorganisms to churn out large quantities of the protein.

Other approaches, even newer, bypass the protein and build vaccines from the genetic instruction itself. This is the case for Moderna and another Boston company, CureVac, both of which are building Covid-19 vaccines out of messenger RNA.

Cepi’s original portfolio of four funded Covid-19 vaccine projects was heavily skewed towards these more innovative technologies, and last week it announced $4.4m (£3.4m) of partnership funding with Novavax and with a University of Oxford vectored vaccine project. “Our experience with vaccine development is that you can’t anticipate where you’re going to stumble,” says Hatchett, meaning that diversity is key. And the stage where any approach is most likely to stumble is clinical or human trials, which, for some of the candidates, are about to get under way.

VIDEO:-How do I know if I have coronavirus and what happens next? –

https://youtu.be/2JsWf-2nN1Y

Clinical trials, an essential precursor to regulatory approval, usually take place in three phases.

The first, involving a few dozen healthy volunteers, tests the vaccine for safety, monitoring for adverse effects.

The second, involving several hundred people, usually in a part of the world affected by the disease, looks at how effective the vaccine is, and the third does the same in several thousand people. But there’s a high level of attrition as experimental vaccines pass through these phases. “Not all horses that leave the starting gate will finish the race,” says Bruce Gellin, who runs the global immunisation programme for the Washington DC-based nonprofit, the Sabin Vaccine Institute.

There are good reasons for that. Either the candidates are unsafe, or they’re ineffective, or both. Screening out duds is essential, which is why clinical trials can’t be skipped or hurried. Approval can be accelerated if regulators have approved similar products before.

The annual flu vaccine, for example, is the product of a well-honed assembly line in which only one or a few modules have to be updated each year. In contrast, Sars-CoV-2 is a novel pathogen in humans, and many of the technologies being used to build vaccines are relatively untested too. No vaccine made from genetic material – RNA or DNA – has been approved to date, for example. So the Covid-19 vaccine candidates have to be treated as brand new vaccines, and as Gellin says: “While there is a push to do things as fast as possible, it’s really important not to take shortcuts.”

An illustration of that is a vaccine that was produced in the 1960s against respiratory syncytial virus, a common virus that causes cold-like symptoms in children. In clinical trials, this vaccine was found to aggravate those symptoms in infants who went on to catch the virus. A similar effect was observed in animals given an early experimental Sars vaccine. It was later modified to eliminate that problem but, now that it has been repurposed for Sars-CoV-2, it will need to be put through especially stringent safety testing to rule out the risk of enhanced disease.

Britain’s Prime Minister Boris Johnson visits to the Mologic Laboratory in the Bedford technology Park, north of London. Photograph: Jack Hill/AFP via Getty Images

It’s for these reasons that taking a vaccine candidate all the way to regulatory approval typically takes a decade or more, and why President Trump sowed confusion when, at a meeting at the White House on 2 March, he pressed for a vaccine to be ready by the US elections in November – an impossible deadline. “Like most vaccinologists, I don’t think this vaccine will be ready before 18 months,” says Annelies Wilder-Smith, professor of emerging infectious diseases at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. That’s already extremely fast, and it assumes there will be no hitches.

In the meantime, there is another potential problem. As soon as a vaccine is approved, it’s going to be needed in vast quantities – and many of the organisations in the Covid-19 vaccine race simply don’t have the necessary production capacity. Vaccine development is already a risky affair, in business terms, because so few candidates get anywhere near the clinic. Production facilities tend to be tailored to specific vaccines, and scaling these up when you don’t yet know if your product will succeed is not commercially feasible. Cepi and similar organisations exist to shoulder some of the risk, keeping companies incentivised to develop much-needed vaccines. Cepi plans to invest in developing a Covid-19 vaccine and boosting manufacturing capacity in parallel, and earlier this month it put out a call for $2bn to allow it to do so.

Coronavirus: the week explained - our expert correspondents put a week’s worth developments in context in one email newsletter

Once a Covid-19 vaccine has been approved, a further set of challenges will present itself. “Getting a vaccine that’s proven to be safe and effective in humans takes one at best about a third of the way to what’s needed for a global immunisation programme,” says global health expert Jonathan Quick of Duke University in North Carolina, author of The End of Epidemics (2018). “Virus biology and vaccines technology could be the limiting factors, but politics and economics are far more likely to be the barrier to immunisation.”

The problem is making sure the vaccine gets to all those who need it. This is a challenge even within countries, and some have worked out guidelines. In the scenario of a flu pandemic, for example, the UK would prioritise vaccinating healthcare and social care workers, along with those considered at highest medical risk – including children and pregnant women – with the overall goal of keeping sickness and death ra tes as low as possible. But in a pandemic, countries also have to compete with each other for medicines.

Chinese President Xi Jinping visits the Academy of Military Medical Sciences in Beijing. Photograph: Ju Peng/AP

Because pandemics tend to hit hardest those countries that have the most fragile and underfunded healthcare systems, there is an inherent imbalance between need and purchasing power when it comes to vaccines. During the 2009 H1N1 flu pandemic, for example, vaccine supplies were snapped up by nations that could afford them, leaving poorer ones short. But you could also imagine a scenario where, say, India – a major supplier of vaccines to the developing world – not unreasonably decides to use its vaccine production to protect its own 1.3 billion-strong population first, before exporting any.

Outside of pandemics, the WHO brings governments, charitable foundations and vaccine-makers together to agree an equitable global distribution strategy, and organisations like Gavi, the vaccine alliance, have come up with innovative funding mechanisms to raise money on the markets for ensuring supply to poorer countries. But each pandemic is different, and no country is bound by any arrangement the WHO proposes – leaving many unknowns. As Seth Berkley, CEO of Gavi, points out: “The question is, what will happen in a situation where you’ve got national emergencies going on?”

This is being debated, but it will be a while before we see how it plays out. The pandemic, says Wilder-Smith, “will probably have peaked and declined before a vaccine is available”. A vaccine could still save many lives, especially if the virus becomes endemic or perennially circulating – like flu – and there are further, possibly seasonal, outbreaks. But until then, our best hope is to contain the disease as far as possible. To repeat the sage advice: wash your hands.

• This article was amended on 19 March 2020. An earlier version incorrectly stated that the Sabin Vaccine Institute was collaborating with the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (Cepi) on a Covid-19 vaccine.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/ ... t-be-ready